Peizazhe të Fjalës is not just a website. It’s a memory machine. In a world that forgets faster than it learns, that might be the most radical thing of all.

In Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino imagines a world of impossible metropolises—each one a metaphor, each one revealing something not about the place, but about the person describing it. Cities made of memories. Cities made of desire. Cities where time collapses. Marco Polo offers these descriptions not to tell Kublai Khan about the empire, but to explain what cannot be said directly.

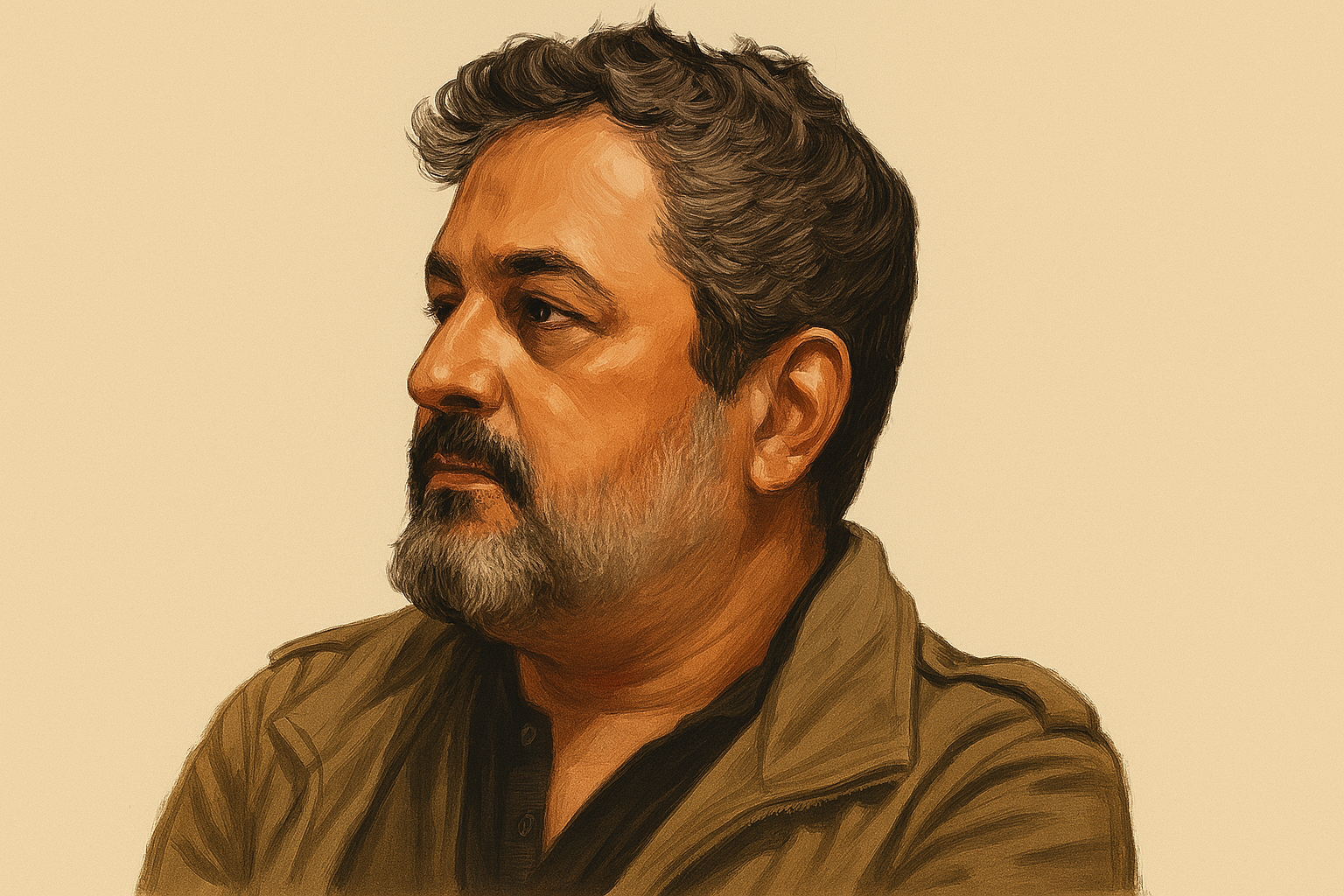

If Albania were one of Calvino’s cities, Ardian Vehbiu would be its cartographer.

For nearly two decades, Vehbiu has been mapping the invisible structures of Albanian life—not its geography, but its rhetoric; not its streets, but its metaphors. He is not a public figure in the traditional sense. He doesn’t command a newsroom or run for office. He has no microphone, no flag. What he has is Peizazhe të Fjalës—Landscapes of the Word—a quiet, persistent digital magazine that has become, in the words of one reader, “a tuning fork for the Albanian mind.”

Vehbiu started the project in 2007, when Albania’s internet was still in its adolescence. “There was a lot of speech, a lot of performance,” he recalls, “but no structure. No place for sustained thinking.” The early 2000s had seen an explosion of commentary—mailing lists, blogs, forums—but the substance, he felt, was thin. So he and a small circle of collaborators built something that didn’t exist: a public space for critical thought. “We weren’t trying to be loud,” he says. “We were trying to be clear.”

The platform they built doesn’t chase the news. It chases meaning. Each day, Peizazhe publishes a long-form essay—on urban memory, nationalism, folklore, language, diaspora. One day, a reflection on post-socialist architecture. The next, a linguistic analysis of a word politicized by the state. The format is deliberate. “We wanted to be somewhere between the Facebook status and the academic paper,” Vehbiu says. “Rigorous, but not rigid. Intellectual, but alive.”

Reading through the archive—which now spans thousands of pieces—is like walking through one of Calvino’s cities. Each text is a corridor of thought, leading into rooms where forgotten ideas are dusted off and held up to the light. One article explores how Albanian nationalist discourse repurposes ancient myths; another revisits the semiotics of Tirana’s clock tower. But it’s not nostalgia. It’s architecture. Vehbiu and his team aren’t mourning what’s been lost. They’re analyzing what’s been built—sometimes badly—and offering a better blueprint.

He describes the project as a form of translation. “Not between languages,” he clarifies, “but between systems of thought.” Having lived in Italy and the U.S., he sees Peizazhe as a bridge—not to the West, but to complexity itself. “We adapt intellectual models to Albanian soil,” he says. It’s like composting. “Ideas don’t import well. They have to be made to grow here.”

That desire for depth—and discomfort—is part of what makes Vehbiu a rare figure in Albanian public life. His personal hero is Slavoj Žižek, and it’s easy to see why. Like Žižek, Vehbiu mistrusts consensus. He pokes at easy narratives. He welcomes contradiction. “We don’t oppose the government,” he says. “We oppose control. That’s what irritates them.”

The irritation has consequences. One article—a clarifying note on the ethnic identity of a historical figure—triggered weeks of vitriol. Vehbiu was accused of betrayal, called anti-Albanian. “It was a linguistic point,” he says. “But it became a nationalist firestorm. I was suddenly criticized for daring to question whether a hero of the Greek Revolution, originating from Medieval Albania, should matter to today’s Albanian immigrants in Greece. That tells you everything about the state of public discourse.”

That discourse, he believes, is in free fall. “There’s a theatricality now,” he says. “Politics as performance. Language as manipulation.” The result is a shrinking of public imagination. “The metaphors they use—it’s like prison slang,” he adds. “Aggressive, juvenile, flat.” In a media ecosystem built for outrage, Peizazhe stands out not because it’s radical, but because it refuses to perform.

This refusal has made it a strange kind of magnet. Policymakers read it. Academics teach it. Students plagiarize it. Many contributors use pseudonyms. Some readers engage quietly. Others, as editor Elona Pira puts it, “read it in secret because they work in government and don’t want to be seen as sympathetic.” And yet, the site endures. Not viral. Not profitable. But necessary.

Vehbiu calls it a “memory machine.” In a country where archives are crumbling and history is contested, Peizazhe has become a public record of how Albanians have thought—carefully, contradictorily, curiously—over the past two decades. “Books disappear,” he says. “Articles vanish. But here, you can read what we were thinking in 2013. You can watch ideas evolve.”

Still, the project faces challenges. Albania’s diaspora, once deeply engaged, is fading into passivity. Nationalist spectacle has replaced public analysis. And funding, never abundant, remains precarious. “It’s free for the reader,” Vehbiu says. “But not for us.” The team considered paywalls, considered Substack. But the goal was never revenue. It was reach. Or rather, depth.

Asked what kind of reader he imagines, he smiles. “Someone who pauses. Someone who stays.” He doesn’t measure success in clicks or followers, but in a quieter form of loyalty: “The reader who comes back years later, with something to say.”

In Invisible Cities, Marco Polo tells Kublai Khan: “The city does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand.” Peizazhe të Fjalës may not tell Albania’s destiny. But it contains its questions, its anxieties, its unfinished thoughts—pressed into the lines of every article.

Because, as Vehbiu knows, nations are not built on declarations.

They’re built on sentences.

And those who dare to write them.

This article reflects the views of the grantees featured and does not necessarily represent the official opinion of the EED.