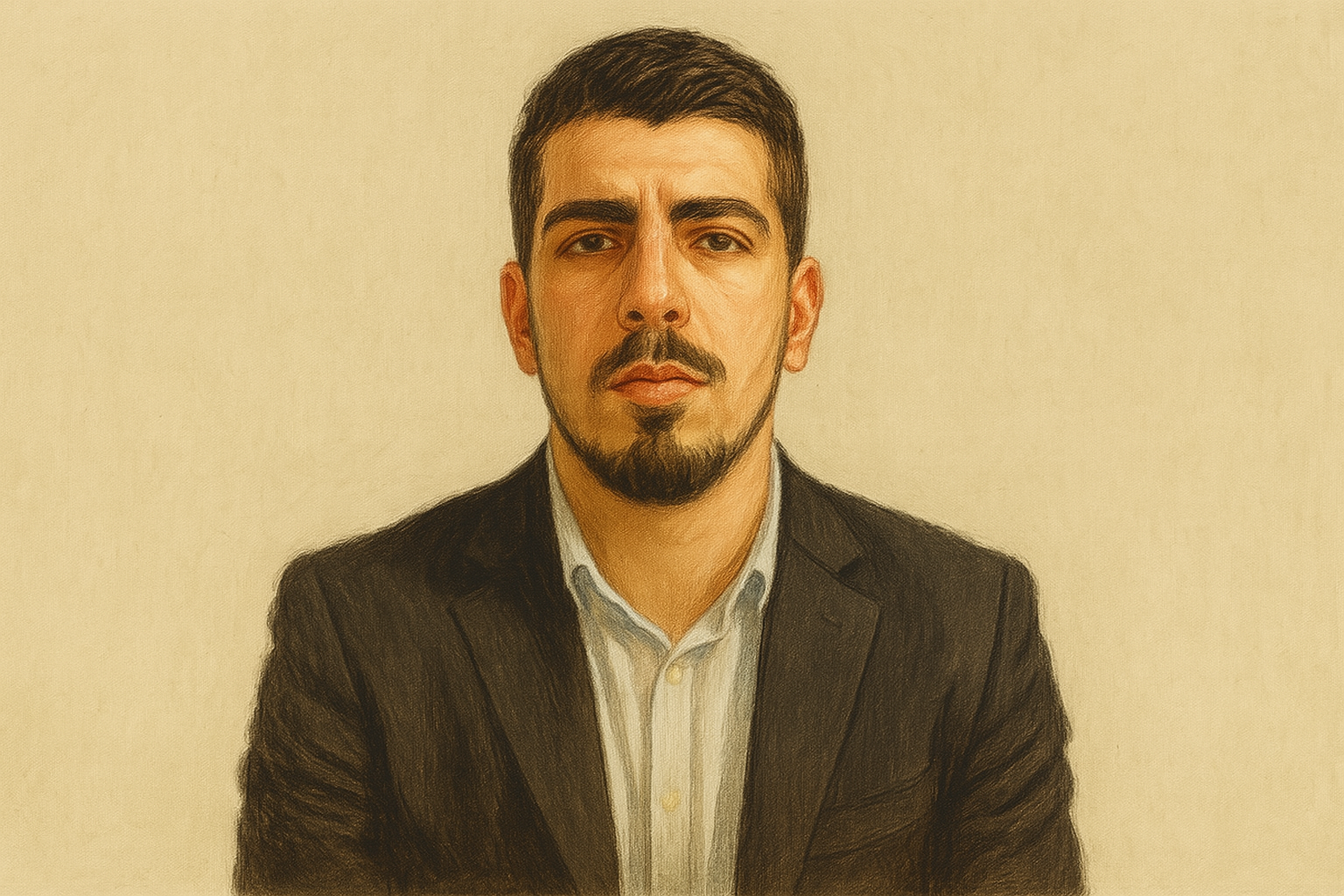

Anesti Barjamemaj is ankle-deep in the Erzen River, navigating the muddy banks near Tirana’s Sharra landfill. He’s alone, carrying a camera and a notebook, trying to document what the state won’t: pollution linked to municipal waste, discharged into a waterway that runs past forgotten neighborhoods. The river stinks. The current is slow. But what flows through it is political — not just environmental.

This is not a symbolic image. It’s fieldwork.

“I needed to take photos and videos from there,” he says, recalling the investigation. “The story brought me to the landfill — and even walking through the riverbed.”

In his nearly ten years as a journalist, Barjamemaj has walked court corridors and protest lines, but he has also walked landfills, riverbeds, and oil-contaminated villages in southern Albania. If most investigative journalism operates from offices in the capital, his begins where infrastructure ends — where residents file complaints in person and institutions have stopped responding.

The riverbed is not where his career began, but it captures something essential about his method: go to the place where systems fail, and start digging.

Barjamemaj’s first investigative piece — published in August 2021 on Reporter.al, part of the BIRN network — focused on Albania’s judicial system and the complex consequences of the 2016 justice reform, a flagship project backed by the European Union and the United States. “I shed light on the judicial system in Albania and the issues caused by the justice reform,” he recalls. “After this investigation, I began to see journalism differently — I understood that this is what I should be doing more of.”

But the more consequential pivot came not in what he investigated, but where.

In 2024, with the EED backing, Barjamemaj launched Gjurmon, an independent investigative outlet based in Vlora. “For years, I had planned to create a local media outlet focused on the Vlora region,” he says. “It was a personal challenge — a response to residents of this area who had long expressed frustration that their problems weren’t being reported by the national media outlets I worked for.”

The name Gjurmon — Albanian for traces or footprints — signals its method and its philosophy. “The gap we aim to fill in Albania’s media landscape is the creation of a small, local, but independent outlet,” he explains.

The selection process for stories reflects that commitment. “Every story covered by Gjurmon is chosen based on the needs of the community,” Barjamemaj says.

“Through field observations, meetings with citizens, and complaints that reach us via our communication channels, we decide what to report on and investigate.”

That logic pushes him into physical and informational terrain that larger national outlets rarely enter. An investigation into pollution in the Vjosa River — a designated National Park — took him to remote villages where oil waste was being discharged into protected waters. In Vlora, he has visited multiple landfills and illegal dumping grounds to track how local waste management intersects with environmental regulation and municipal contracts.

These aren’t stories of individual scandal. They are stories of state dysfunction, parsed locally and built from the ground up.

This method — immersive, citizen-responsive, geographically embedded — contrasts sharply with the prevailing media model in the Balkans. “Investigative journalism in the region is losing ground — primarily due to lack of funding,” Barjamemaj says. “Only a few media outlets have been able to resist pressure and maintain such independence.” He points to the closure of INA Media as a cautionary case. “It left a significant void.”

That void is institutional — but also civic. Journalism, as Barjamemaj practices it, isn’t just about informing the public. It’s about building mechanisms of accountability where formal ones have failed. “Our aspiration is to build a sustainable media outlet that reaches beyond the Vlora region,” he says. “We aim to transform Gjurmon into a fact-checking and watchdog media outlet monitoring the work of both local and central authorities.”

In five years, he says, Gjurmon will be “one of the most important media platforms in Albania within the fact-checking and watchdog genre.” It’s not a boast. It’s a hypothesis — one built on the assumption that democratic oversight still matters.

This approach extends to questions of journalistic ethics. When asked about neutrality, he’s direct: “My guiding principle in daily work is: if you stick to the facts — and only the facts — you are neutral.” He sees neutrality not as disengagement but as methodological rigor — a tool to resist political instrumentalization.

Still, he’s aware of the deeper crisis: truth is no longer self-evident. “I believe people are seeking the truth more than ever,” he says. “The truth is hard to find today — which is why, despite losing some of its power, media still holds an unmatched ability to reveal it.”

When asked what story he would investigate if he faced no limitations, he doesn’t hesitate: “I’d want to write a global investigative story about the misuse of public funds by officials in every country.” The answer may sound broad, but it is consistent with his local practice. Corruption is not abstract. It is material, relational, and cumulative — built riverbed by riverbed, landfill by landfill, village by village.

His answers to personal questions are similarly utilitarian. Hero? “A hero is anyone who does what should be done — not what shouldn’t.” Superpower? “To be invisible — and hear what politicians really think about their citizens.”

That last line could be a manifesto. Like a skilled detective, Barjamemaj isn’t driven by spectacle or confrontation. His work relies on patience, proximity, and attention to what isn’t said. To investigate, for him, is to observe what’s hidden in plain sight: the distance between official statements and lived experience, the quiet spaces where power leaves its trace.

It’s a method. It’s a posture. And in Barjamemaj’s case, it’s a career built one muddy step at a time — from the riverbed up.

This article reflects the views of the grantees featured and does not necessarily represent the official opinion of the EED.